Invented by accident: The incredible story of how TV dinners conquered the world

1950s Unlimited/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

How the TV dinner changed mealtimes forever

When the TV dinner came onto the scene in the 20th century, it would shift the West's approach to dining forever. From the first meat-and-veg-filled metal tray, to today's creative approaches, we chronicle the life of the TV dinner from the 1940s to the present day.

University of Washington/Flickr/CC0

Take off

While credit for inventing the beloved TV dinner is usually given to long-standing frozen-food company Swanson, there were actually earlier iterations. The very first TV-dinner-style meals – including a compartmentalised aluminium tray laden with meat and two veg – were manufactured shortly after WWII by Maxson Food Systems Inc, and were served on Pan American Airways.

Sir Beluga/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

An early iteration

In 1949, still around half a decade before Swanson had TV dinners on their mind, brothers Albert and Meyer Bernstein took a stab at the frozen-meal market. They established themselves as the Quaker State Food Corporation – and though they didn't take their business beyond the Pittsburg area, by 1954 they'd sold a whopping 2.5 million frozen dinners. It was clear that there was a decent appetite for these convenient meals.

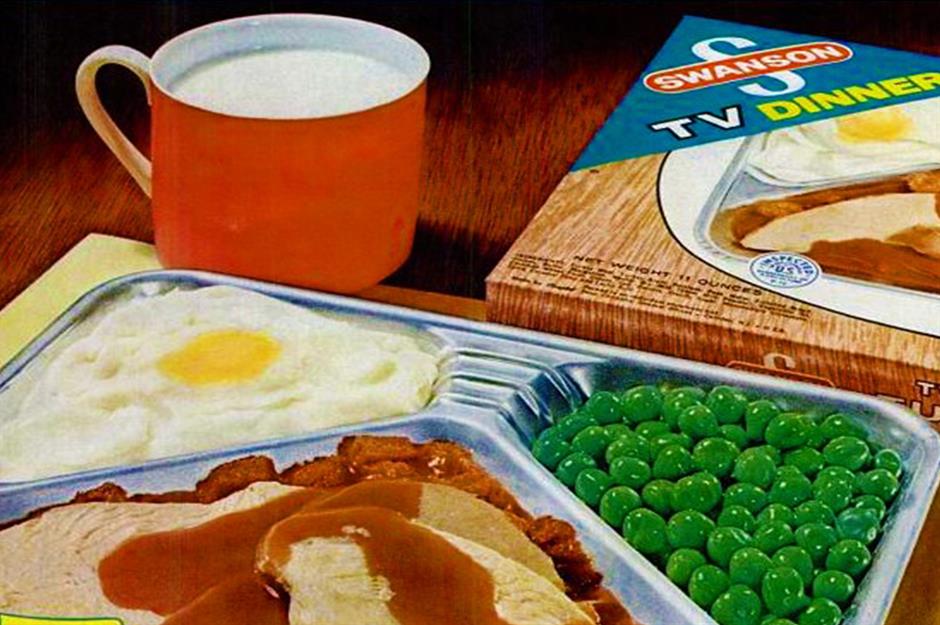

1950s Unlimited/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Swanson is on the scene

Despite these earlier attempts to crack the ready-meal market, it was frozen-food heavyweight Swanson who had the ingenuity and the marketing prowess to win America over. They launched their product with an elaborate campaign and a neat name to sum up their invention: The TV dinner.

Africa Studio/Shutterstock

A Thanksgiving mix-up

Nevertheless, Swanson's TV dinner may never have happened if it wasn't for a business blunder that left the company with some 520,000 pounds of turkey left over after Thanksgiving in 1953. Dismayed bosses asked staff to think of a clever way to stop the meat from going to waste. It was salesman Gerry Thomas who purportedly came to the rescue.

Sensei Alan/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

A neat idea

Inspired by the meals served on a recent Pan American Airways flight he'd travelled on, quick-thinking Thomas pitched the idea of a frozen dinner to bosses. He proposed a metal tray perfectly sized to plate up a full evening meal and designed so it could comfortably sit atop a customer's lap while they watched TV: Something that was becoming an increasingly popular pastime during this era. Relieved, top dogs loved Thomas's idea and set about getting his vision into shops.

Sensei Alan/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

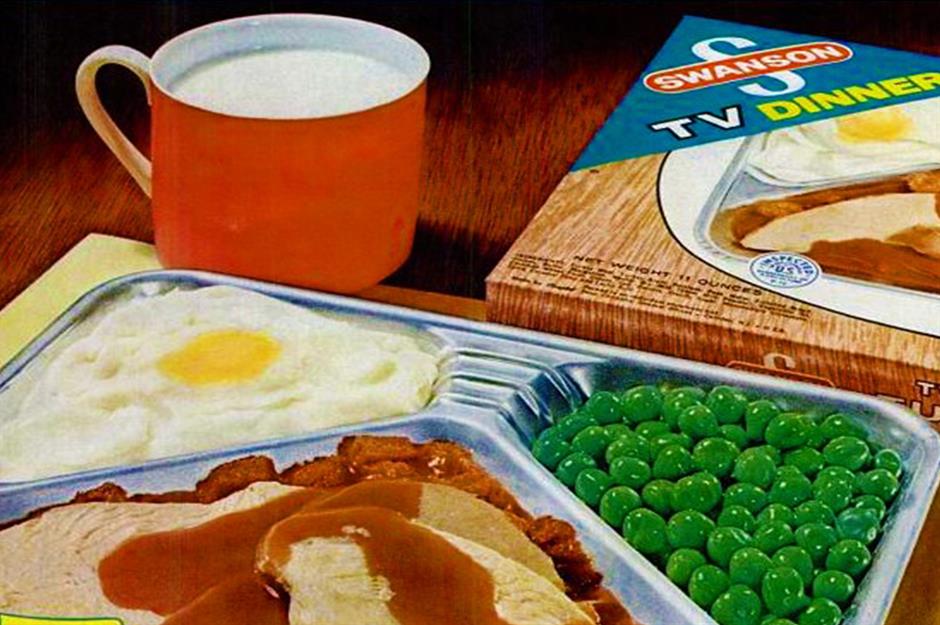

America's first TV dinner

The final design was the vision of Betty Cronin, a bacteriologist working for Swanson at the time. She and her team worked hard to iron out the kinks, such as varying cooking times among food items. The result was America's first official TV dinner, with turkey and gravy, sweet potato and peas. It was neatly packaged in boxes made to look like televisions – complete with tuning knobs and all – and sold for $0.98 a piece. A mere 25 minutes in the oven, and you had yourself a turkey dinner.

Evert F. Baumgardner/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

Right on the button

Swanson couldn't have struck at a better time. The television – considered a gloriously Jetsonian invention at this point in time – was rapidly gaining in popularity, and more and more households were giving them pride of place in their living rooms. In fact, more than half of Americans had a TV in their home by 1954, compared to just 9 percent some four years earlier.

Quin Dombrowski/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

A growing appetite

The public relished Swanson's offerings, and in the first year alone, more than 10 million TV dinners were sold in the USA. America's dining habits had changed forever.

Steven Labinski/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

A recipe for success

The TV dinner industry burgeoned from there onward. Other brands took a bite out of the ready-meal hype, and by the end of the 1950s, Americans were spending some half a billion dollars on these convenience foods each and every year.

theimpulsivebuy/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

A mini Banquet

One of the first brands to follow Swanson's lead was Banquet – founded in 1953, they originally sold frozen meat pies. But when TV dinners took off, this relatively new company wanted a slice of the action. Hot on the heels of market leader Swanson, they began selling their own versions of the trademarked TV dinner in 1955. Their offerings included crispy southern-fried chicken with creamy mash and greens; and Salisbury steak with mash and corn.

Something from Stouffer's

Next on the gravy train was Stouffer's. Dating back to 1924, and seeing many iterations over the years, Stouffer's first started selling frozen dinners to punters at their Cleveland restaurant, so customers could enjoy the venue's offerings at home. But noticing the soaring popularity of the frozen ready meal, Stouffer's decided to go bigger and by the 1960s their TV dinners were also on supermarket shelves. Classics included baked and fried chicken; and mac and cheese.

Sensei Alan/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Beefing things up

While competition arose all around, Swanson busied themselves with improving and expanding upon their selection. They added varieties such as meatloaf, steak and fried chicken, all served with potatoes and assorted veggies. By the early 1960s, they'd also added a dessert compartment. In a bid to encourage consumers to eat these convenient meals anytime of day, Swanson also dropped TV dinner from its packaging – but by now it was a term embedded in the American psyche.

Nationaal Archief/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

A different kind of meal time

The TV dinner would change the fabric of family life in the States. Previously, dinner was a family affair in which the entire clan would gather around the table and swap stories about their days. The advent of the TV dinner, however, and the rising profile of the TV itself, represented a shift towards screen-time over conversation, and convenience over home cooking. A 2015 study by the Food Marketing Institute showed that today, almost 50 percent of all meals and snacks are consumed in solitude in the USA.

Nationaal Archief/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

A frozen time saver

But not everyone was happy. Women were the primary housekeepers in this era, spending an average of four hours preparing food and cleaning up afterwards. Swanson was purportedly inundated with angry letters of complaint from husbands, lamenting their being given a TV dinner in place of a home-cooked meal. The TV dinner was a pivotal factor in the changing way households were run. Today, the average American woman spends some 45 minutes cooking and washing up (still more than the typical male's 15 minutes).

Internet Archive Book/Flickr/CC0

Across the pond

The TV dinner phenomenon eventually made its way across the pond, though a ready-meal craze didn’t truly grip Brits until the late 1960s – this was because many a British kitchen lacked a domestic freezer until then. TV dinners began thriving in Britain through the 70s and into the early 80s, with companies such as Birdseye at the helm. According the BBC, the growing sales were in part due to rising divorce rates – savvy ready-meal companies marketed their products with single men in mind.

A chilled-out approach

However Brits soon fell out of love with the traditional frozen TV dinner, preferring a chilled convenience meal instead – the first of these was launched by M&S in 1979. Today, Britons still eat more ready meals than anywhere else in Europe, consuming on average one per week (this is followed by ready-meal-loving France, Germany and Spain). And the appetite for these meals shows no sign of letting up: across the continent, the market has seen steady growth for years.

Richard B. Levine/SIPA USA/PA Images

Bigger and better

By the early 1960s, the TV dinner got a supersized makeover. Campbell Soups Company, Swanson's parent company at the time, added the Hungry Man to their food portfolio. An oversized version of Swanson's original TV dinners, the Hungry Man was designed for big appetites. Early meals included a chunky steak with brownie for dessert; and a fried chicken dinner complete with crinkle cut potatoes, corn and apple-raisin cake cobbler.

Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock

A new kind of oven

The arrival of the microwave revolutionised the TV-dinner industry too. The first household microwave model was completed in 1967 by appliances company Amana, and they rapidly gained in popularity throughout the 1970s. In 1986, Swanson responded by swapping their long-used metal tray for a plastic one suitable for microwaves. This soon became an industry standard.

Thomson 200/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

Getting leaner

By the 80s, diners were craving something more from their meals, and society was becoming more health conscious. Lean Cuisine (sister brand to Stouffer's, by then owned by Nestle) began in 1981. Their meals were marketed as light alternatives to Stouffer's calorific suppers, with less than 300 calories and a free dieting book thrown in, too. The upmarket Le Menu range from Swanson was also born: It matched the meat-and-two-veg template but with options such as orange chicken or pepper steak.

Shoshana/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Amy's is born

In 1987, Amy's came onto the scene too. Touting itself as an antidote to the bigger brands' artificial flavourings and preservatives, Amy's professed to use only natural ingredients, was completely meat-free and also included a sizeable gluten-free range. The first product was a warming veggie pot pie – it flew off the shelves and the brand has flourished ever since.

Karin Dalziel/Flickr/CC BY-NC 2.0

Recognising an icon

By the late 80s, with so many frozen-dinner brands competing for space in the market, the original Swanson product had taken on a kind of nostalgic air. The metal tray in particular had become an American food icon, and an early model was snapped up by the Smithsonian Institution for display. By 1999, Swanson had also earned a star along Hollywood's Walk of Fame.

An upscale TV dinner

Other big brands also capitalised on the TV dinner's nostalgic quality. In 2008, the stylish Loews Regency Hotel (New York City) put on their own fancy TV dinner, complete with a porcelain tray, all charged at a price of $30. Guests could choose from a pinot-noir braised pot roast or free-range chicken, and sides included mac and cheese with cheddar, Swiss, asiago and parmesan. Needless to say, it went down a treat.

Cultura Motion/Shutterstock

Screen time

It's clear too, that beyond the nostalgia, the TV dinner has had a lasting impact on society. Today, according to the Statistics Brain Research Institute, two thirds of Americans eat their dinner in front of the television. Meanwhile, a study by Co-op Food showed that in Britain, more than half of the population have a screen present during mealtimes, and the average dinnertime lasts just 21 minutes.

Lynne Ann Mitchell/Shutterstock

The end of the TV dinner?

But, despite this, for a long time it looked as though the future might be fresh rather than frozen. After some 60 years of steady growth, frozen dinner sales fell into decline between 2008 and 2016. Harvey Hartman, founder of market research company The Hartman Group, said that the TV dinner is losing relevance in a modern society. He told AdWeek: "Younger consumers want fresh ingredients, mobile use is supplanting TV time and "dinner" increasingly means a late-night snack."

Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock

Diners about town

We're also eating out more. In the 1960s, only a quarter of the money spent on food was spent at restaurants, cafés or similar: the onus was on cooking and eating at home. Fast-forward almost six decades and this stat has been flipped on its head. Americans and Britons now spend more money on restaurant food and takeaways than they do in grocery shops – so it's no wonder that the love affair with the frozen TV dinner appears to be at its melting point.

Special delivery

Another factor is the gaining popularity of meal-kit delivery services such as Blue Apron and Hello Fresh – some have even dubbed meal kits the modern version of the TV dinner since they couple convenience with the present-day priority of freshness and meals made from scratch. Almost 27 percent of internet users purchased these kits in 2016, and the industry was then worth $1 billion dollars – this is projected to rise to $10 billion by 2020.

Jonathan Feinstein/Shutterstock

Upping their game

But traditional TV-dinner brands aren't giving up without a fight. Swanson, Banquet and Stouffer’s are all still running, and they're doing their best to adapt to a modern market. Banquet, in particular, has kicked things up a gear, gracing TV screens with a brand new advert in 2016 (the first in more than seven years). The message was "Now Serving a Better Banquet," with tweaks including swapping out dark meat for 100 percent chicken breast and putting real cream and margarine in the mash.

Richard B. Levine/SIPA USA/PA Images

A new brand of TV dinner

The Frozen Food Institute has also stepped up: their campaign "Frozen: How Fresh Stays Fresh" urges Americans to fall in love with frozen food again. A new crop of 'freshness'-focused TV dinner brands, keen to challenge perceptions, have cropped up, too. These include plant-based Sweet Earth, and EVOL, producing antibiotic-free, preservative-free meals – both were launched in 2002. Devour was started by The Kraft Heinz Company in 2016 and aims to put restaurant-quality meals in frozen packages.

A frozen future?

It seems the effort is working. In 2016, sales of frozen ready meals grew in the USA for the first time in nearly a decade – so it seems that America's love for the TV dinner hasn't thawed just yet...