Food brands that came back from the brink

Biting back

It seems we really don’t know what we’ve got until it’s gone when it comes to food. Or, at least, until it’s nearly gone. Some of the most iconic food brands have come close to disappearing from the shelves, saved with a last-minute reprieve by investors or through a crowdfunding campaign. Others have been discontinued only to reappear, in some cases decades later, thanks to public demand. Here are some of the food brands that were nearly lost forever.

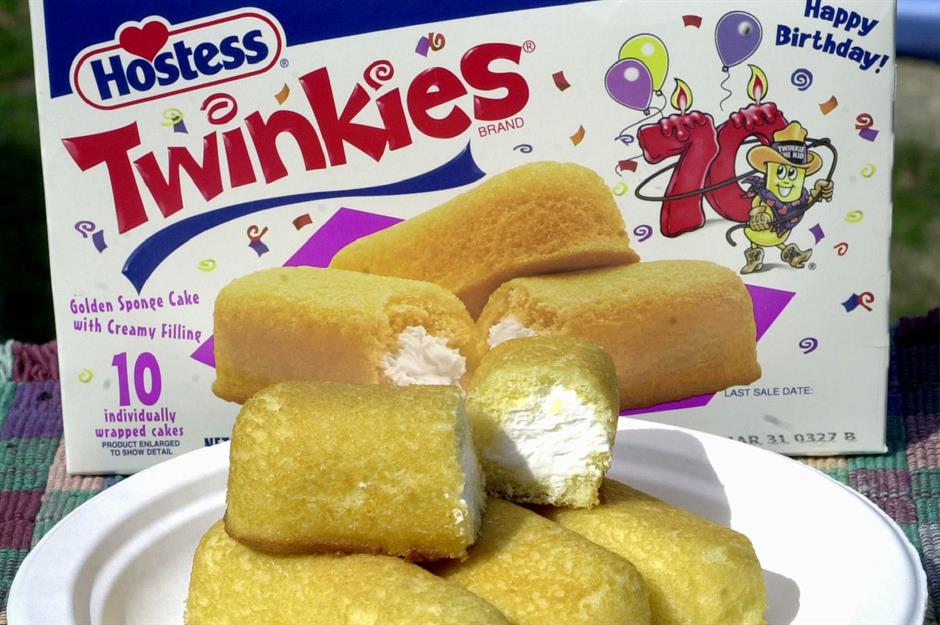

Hostess

Few foods are so ingrained in US culture as Twinkies, the snack-sized cakes filled with vanilla cream and – if you believe the movies and television – regularly consumed by cops. Yet they nearly disappeared in 2012 when owners Hostess filed for bankruptcy. The company, which was founded in 1930 and also produced Wonder Bread, Ho Hos and Ding Dongs, had already folded once before in 2004, when it blamed falling sales on low-carb diet trends. This time it was high pension costs and the rising prices for ingredients including flour and sugar.

Hostess

The Texas-based company, whose Wonder Bread was among the first sliced loaves sold in US supermarkets, was sold to a private equity firm and was later acquired by Gores Holdings Inc. to become a publicly traded company. Twinkies and other Hostess snacks returned to the shelves in summer 2013, much to the delight of fans who had been outraged by their hiatus.

New England Confectionery Company

This Revere, Massachusetts-based company – better known as Necco – closed in July 2018, just months after being saved from bankruptcy by investment company Round Hill. The news signalled the end of the USA’s oldest continuously-running candy company as well as the disappearance of some much-loved sweet treats. Necco began in 1847 and was known for Sweethearts, Wafers, Clark Bars and Mighty Malts.

New England Confectionary Company

The brand was later bought by Spangler Candy Company, which announced plans in 2020 to relaunch one of the company’s most popular products, Necco Wafers. These round, pastel-hued candies are sold wrapped in wax paper and come in flavours including lemon, orange, clove, cinnamon and chocolate. Spangler’s CEO described them as a “comfort food” to bring the “familiar, comfortable feeling” people are craving.

Starbucks

It’s hard to imagine a city or perhaps even a street without a Starbucks, but the coffee chain hit serious problems in 2008. The company, which was founded in 1971 in Seattle, Washington and has shops in all 50 states plus more than 40 other countries, was badly hit by the economic downturn. Profits dipped by 28% in 2008 compared to the previous year, and it closed a total of 900 stores by 2009. Stock prices hit a low of just under £3 (around $4) compared to more than £11 ($15) in 2006.

Starbucks

Howard D. Schultz returned as CEO after an eight-year hiatus and is widely credited with pulling the company back from the brink. Schultz believed the chain had expanded too rapidly and lost its connection with customers and the community. He launched an online community and idea-exchange portal, “My Starbucks Idea”, to increase engagement with customers and boost the brand’s presence on social media. The company has suffered further losses and closed stores due to the impact of COVID-19, though closed out 2020 with an all-time-high stock price of £77 ($106).

Viennetta

With its soft waves of ice cream layered with chocolate that cracks against the spoon, Viennetta has been a true British favourite since being launched by Wall’s in 1982, initially as a special release for Christmas. But, though it’s still a staple ready-made dessert in the UK (seeing success with its retro appeal), it somehow failed to fully crack the US. Unilever launched the indulgent ice cream in the US in the mid-1980s and, though it was initially popular, it was discontinued a decade later.

Viennetta

Many fans mourned the demise of the luxury, delightfully decadent dessert and its famously over-the-top adverts. But it took nearly 30 years for Unilever to bring it back to the US, driven by customers’ appetite for all things retro. The company announced the ice cream brand's comeback in January 2021, with a classic vanilla “ice cream cake” to be manufactured by Good Humor.

SodaStream

SodaStream will perhaps always be associated with the 1970s and 1980s, when families were encouraged to “get busy with the fizzy” – and at the time, 40% of UK households did just that by owning one of the water-carbonating machines. But it’s actually been around since 1903 and has been through several owners, including Cadbury Schweppes, who bought it in 1985, and Israeli distributor Soda-Club in 1997. It slid into near-obscurity in the following years and seemed destined to be a relic of the past.

SodaStream

Then, in 2007, Israeli private equity firm Fortissimo Capital purchased the company and hired Nike executive Daniel Birnbaum as CEO to give the brand a boost. The revamped machines were soon stocked by US retailers including Bloomingdale’s and Williams-Sonoma, and PepsiCo bought the rights to the brand in 2018 for £2.5 billion ($3.2bn).

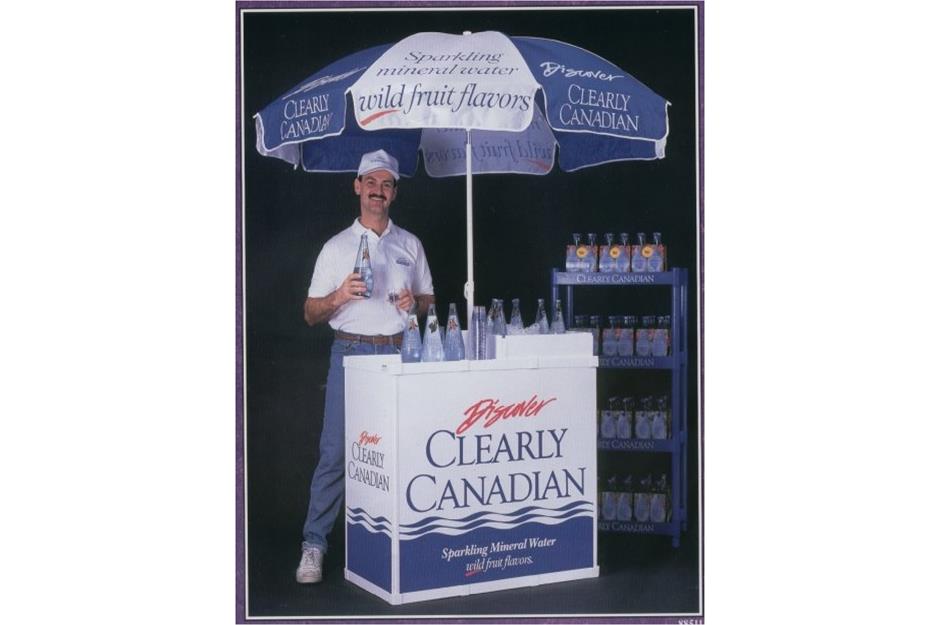

Clearly Canadian

This clear, fruit-flavoured sparkling water was perhaps a little ahead of its time when it was launched in 1988. Clearly Canadian was initially successful and achieved sales of more than £86 million ($150m CAN) in 1992. But its fall was as dramatic as its rise and profits plummeted. Analysts suggest people felt misled by the brand’s marketing as the product was more akin to soda than water, while others blamed mismanagement. The bottles disappeared from shelves in 2009.

Clearly Canadian

It was a crowdfunding campaign led by venture capitalist Robert R. Kahn, who purchased the Vancouver-born brand, that led to the drink's return in 2015. Under Khan, Clearly Canadian launched a pre-order campaign in February 2014, selling more than 40,000 cases within weeks, according to the website. It was later rolled out to stores in Canada and the US.

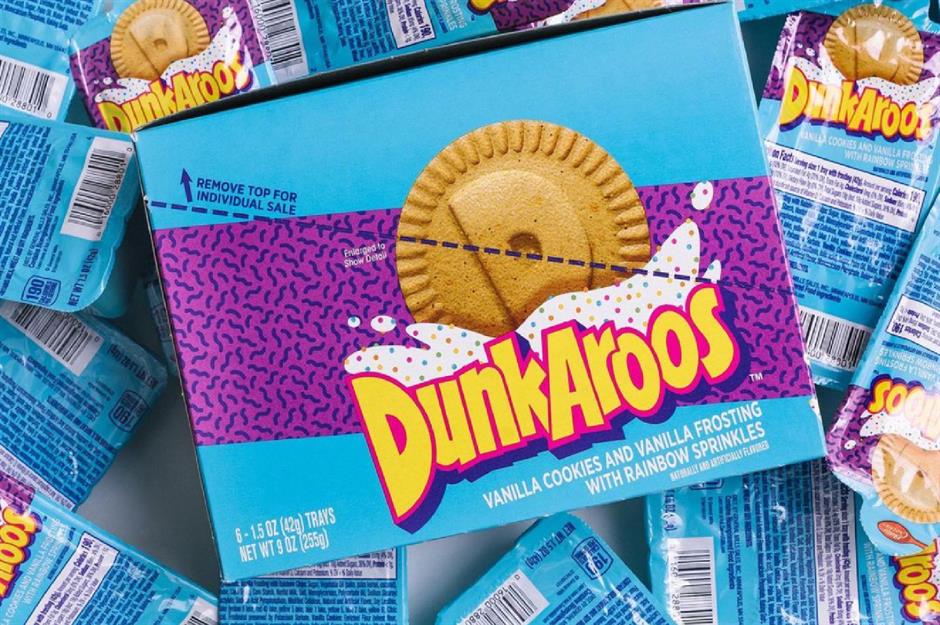

Dunkaroos

Dunkaroos were a classic snacking choice in the 1990s, with kids especially loving the combination of mini cookies with a tub of frosting (for dipping) on the side. So their disappearance from the US market in 2012, while remaining on sale in Canada until 2017, caused some upset. The brand’s parent company, General Mills, said it was due to focusing on healthier snacking in the US, though they were inundated by customer requests to bring them back.

Dunkaroos

General Mills teased the return of the retro snacks by launching Dunkaroos social media accounts, followed by a blog post announcement in early 2020. The first product back on the market was vanilla cookies with a dip of vanilla frosting with rainbow sprinkles. They’ve now added extra treats to the brand, including cookies with yogurt dips, cookie dough and a brand-new Dunkaroos cereal, with mini frosted cookies designed to be drenched in milk and eaten by the spoonful.

Kiddyum

This kids’ food brand was founded in 2011 in Manchester, England, and produced healthy frozen meals made with natural ingredients and free from preservatives, and genetically modified and artificial flavourings and colourings. The meals were sold by supermarkets Sainsbury’s and Co-op, as well as online grocery retailer Ocado. But the company struggled to make a profit and eventually went into liquidation in August 2020.

Kiddyum

The brand was granted a reprieve weeks after its collapse, with potato supplier Albert Bartlett buying Kiddyum. The purchaser already owned 40% of the company following a deal in late 2019. It plans to keep the meals – which are designed for children aged between one and four years-old – listed with the same sellers, while also working to get them in other stores.

Bagel Nash

It was COVID-19 that caused Bagel Nash to struggle. The company, founded in Leeds, England in 1987, produced more than 20 million bagels per year and supplied the food service industry in the UK and 20 other countries. The closure of restaurants, cafés and hotels during the various lockdowns from March 2020 onwards caused severe cashflow problems and the company went into administration that August.

Bagel Nash

It was swiftly rescued by Golden Acre Bakery, who purchased the business and assets under the umbrella Golden Acre Food Group and also kept on the company’s 52 employees. Golden Acre supplies major wholesalers with both branded and private label goods including Urban Active protein shakes and Golden Acre yogurts. The sale didn’t include Bagel Nash’s 11 retail shops in northern England, which are currently still operating.

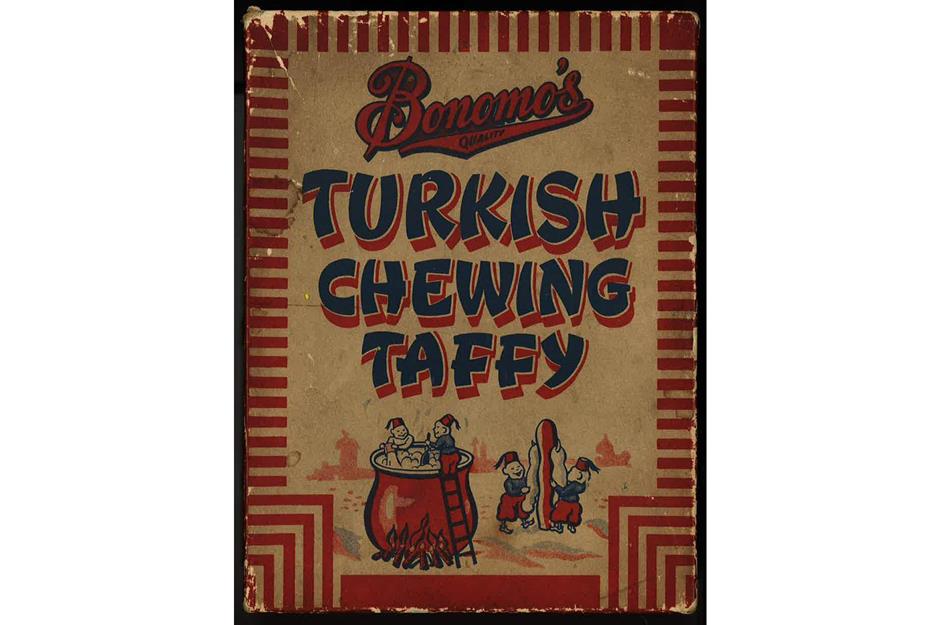

Bonomo Turkish Taffy

Everything about Bonomo Turkish Taffy says classic seaside. It was invented on Coney Island, New York in 1912 when candy maker Herman Herer accidentally added too many egg whites to a batch of marshmallows, creating a stretchy, sticky, chewy sweet treat. The taffy even had its own TV show, The Magic Clown, from the late 1940s until 1959. The taffy bars and twists became huge sellers across the US until the 1970s, when Tootsie Roll Industries purchased the taffy, changed the recipe and rebranded it, before shelving it altogether.

Bonomo Turkish Taffy

The original taffy still had a huge fanbase and there were petitions to bring back the brand. It was eventually purchased by entrepreneurs (and taffy fans) Kenny Wiesen and Jerry Sweeney in 2002, and returned to its original formula. The taffy was relaunched eight years later in bars and twists in vanilla, strawberry, chocolate and banana flavours, with consumers once again encouraged to crack the bars into bite-sized pieces.

Take a look at the vintage food brands that deserve a comeback

Urban Eat

This range of pre-packaged sandwiches was part of Adelie Foods, a company specialising in to-go foods. Adelie, which was the UK’s third-biggest sandwich maker, had reported losses from 2016 onwards and blamed pricing pressures for plummeting profits. The company’s food service business also disappeared during the COVID-19 crisis, and the company went into administration in May 2020, owing around £100 million ($137 million) to its private equity owner as well as suppliers and employees.

Urban Eat

Urban Eat was snapped up by Samworth Brothers, which owns Ginsters – known for pasties – and Soreen malt loaf. The rescued brand’s products fall under four ranges: Core, which consists mainly of sandwiches, the health-focused Roots range, the Deli items and Street, inspired by street food. They’re mostly sold in convenience stores and cafés. Other Adelie brands including Winterbotham Darby, which sells olives and antipasti, were sold to five different buyers.

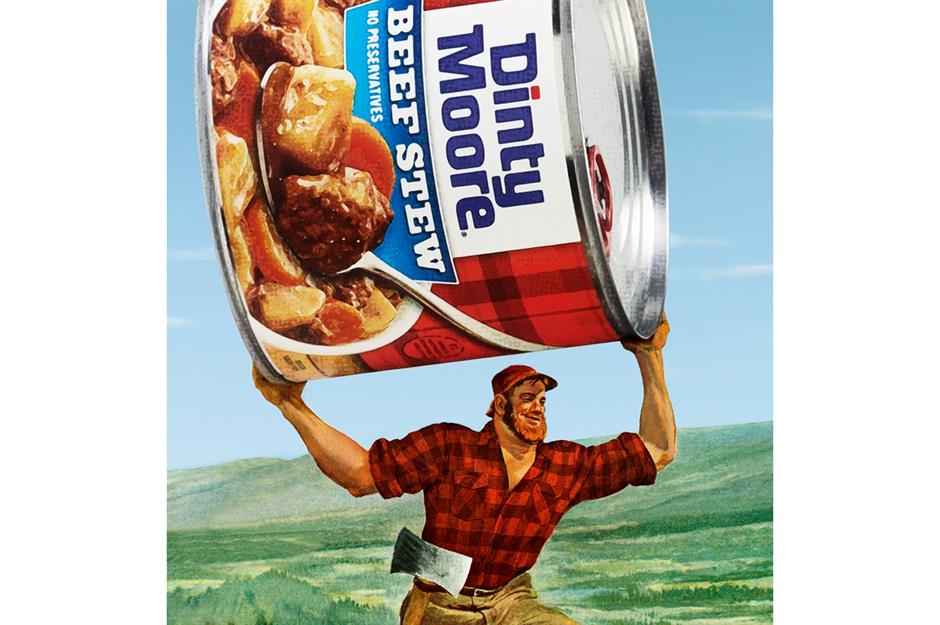

Dinty Moore

This stew brand, owned by Hormel Foods, was launched in 1935 when the US was in the midst of the Great Depression and quickly became a favourite when it came to easy, affordable, filling meals. It remained the market leader in the early 21st century but suffered as the stew category overall declined by around 20%. The stew, with meat, potatoes, gravy and carrots, had been all but forgotten by consumers.

Dinty Moore

Rather than abandoning the brand, Hormel – whose other brands include Spam – launched a campaign reaffirming Dinty Moore as a hearty meal, with tongue-in-cheek ads featuring lumberjacks that earned the brand an Effie, known as one of the top marketing awards. They also introduced microwavable trays and bowls alongside the original tins in a bid to broaden the appeal. By 2018, sales had boosted by 18%.

Check out the fast food brands everyone loved the decade you were born

SnackWell’s

This healthier snack brand was launched in 1992, when better-for-you and low-fat foods were at peak trendiness. Its fat-free cookies were initially a huge hit but increasing competition led to a decline in sales by the end of the decade and its market share continued to drop into the new millennium. The snacks were reformulated in 2015 to strip out high-fructose corn syrup and artificial ingredients, but sales still flailed.

SnackWell’s

The brand was picked up in 2017 by B&G Foods, which has a track record of acquiring and turning around struggling brands including Victoria’s sauces and Green Giant. B&G also purchased SnackWell’s fellow better-for-you snack producer, Back to Nature, which encompasses granola, crackers and cookies.

Frank Dale Foods

Many people who have tasted Frank Dale Foods probably haven’t heard of them, because the Norfolk, England-based manufacturer makes party foods sold under various labels at supermarkets including Sainsbury’s, M&S, Morrisons and Tesco. And the canapé producer, which makes a range of sweet and savoury bites, nearly disappeared altogether after recording a £500,000 ($682,000) loss in 2016 and entering liquidation. The company blamed production issues, which meant orders went unfulfilled.

Frank Dale Foods

It was a last-minute reprieve in early 2017 that saved the brand, with the just-formed Finedale Foods buying the company and promising to secure most of the 57 jobs. Its first-year profits following the acquisition were £550,000, signalling a significant turnaround after the previous losses. The brand has struggled with lack of demand due to COVID-19 and is now pivoting with direct-to-consumer sales of its mini products like quiches and coffee cakes.

Campbell Soup

Campbell Soup – owner of the iconic (and pop-art famous) condensed soups and other food products – had suffered declining sales in the past few years, with shares falling 20% in 2018 based on the previous year. Alleged internal rows over whether to abandon the core products and focus on more modern brands, such as V8 vegetable juice, exacerbated the situation and investors pressured the company to sell. There were also issues with acquisitions including snack brand Snyder’s-Lance, with the CEO stepping down.

Campbell Soup

One reason suggested for the slump was that fewer people were working from home – which changed dramatically due to COVID-19. While many brands have suffered due to the pandemic, Campbell Soup has proved a lockdown hit as consumers look for comfort, familiarity and convenience. The company reported a 35% increase in its sales of soup in the US alone in the first quarter of 2020, with its snacks including Goldfish crackers and Cape Cod crisps also boosted.

Now read the legendary fast food brands we wish would make a comeback

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature

Most Popular

Reviews 31 unbelievably sugary cereals from around the world