The secrets behind food labels you need to know

What's in a label?

Supermarket shelves are packed full of foods and drinks bearing labels with reams of information, lengthy ingredients lists and health-boosting claims. With so much information (and disinformation) available, it can be confusing to know which products to choose, and which to leave behind. With exactly that in mind, here we reveal the most common food label secrets you need to know about.

Click or scroll through our gallery to discover the food label secrets hiding in plain sight.

'Organic' might not mean what you think it means

In both the US and UK, food labelled as organic has to contain at least 95% organic ingredients; however, something labelled as 'made with organic ingredients' can contain up to 30% non-organic ingredients. Be aware that 'organic' doesn't necessarily mean healthier across the board, either – the label has nothing to do with the calories, fat, carbs or sugar present in the food.

'Free range' is a complex term

These days, we're pretty clued up on animal welfare; we know that higher quality products generally mean a higher quality of life for the animals. But nothing is as straightforward as that. For a product to be labelled 'free range', the animal has to have access to an outside area for at least part of the day. However, in the US there’s no specification as to the length of time, so this could be as little as five minutes. Meanwhile, in the UK, the rules are stricter – look out for the Soil Association label for eggs from much happier hens.

Natural doesn't really mean anything

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), when the term 'natural' appears on a product, it doesn't necessarily mean much. For example, some processed products, including lemon-flavoured Oreos, Skippy peanut butter and certain types of Cheetos, all have the word 'natural' written across their labels. In the US, policies regarding the 'natural' label do not relate to the use of synthetic pesticides, hormones, antibiotics and genetically modified organisms in livestock and crops. In short, if you’re surprised that a product carries a ‘natural’ tag, it probably doesn’t deserve it.

Ingredients are arranged by weight

Ingredients lists can tell us many things about the product we're about to buy. But did you know that the order in which the ingredients are listed is important, too? In most countries, the ingredients are arranged by weight, in descending order. In other words, the main (or dominating) ingredient will always be listed first. For example, if you're buying tomato sauce and tomatoes appear way down the list after water and oil – or if avocado isn't listed as the first ingredient in guacamole – you might want to consider giving them a miss.

‘Fruit-flavoured’ doesn't mean healthy

Sometimes it's hard to resist a zingy yogurt or a fruity beverage. However, you might want to think carefully about selecting products labelled as 'fruit-flavoured'. A lot of these products don’t contain any fruit at all – and they're often loaded with both sugar and chemicals, rather than the natural ingredients the label suggests. Switch out your morning fruity yogurt for a plain variety and add in fresh fruits instead, or look at the labels carefully to find products containing real fruit juices and pieces.

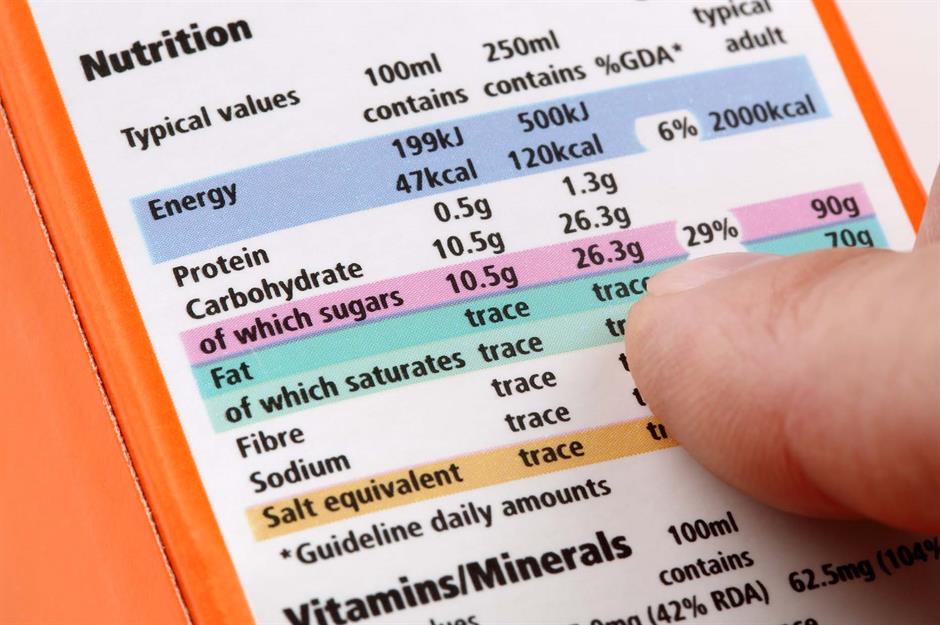

Low fat and low sugar aren't necessarily a good thing

There's a very simple explanation as to why these terms aren’t particularly relevant if you're looking to improve your diet. For a product to still taste great, when something is taken away, something else is usually needed to replace it. In low-sugar or sugar-free foods, it's usually more fat and other additives – while a lack of fat in low-fat foods is often disguised with large amounts of sugar. The best thing you can do here is to always read the nutritional breakdown carefully and make your selections accordingly.

Zero doesn't always mean zero

If a product's label says it contains zero sugar or zero fat, you might assume there's none of it in the product – but it's not quite as straightforward as that. In the US, the FDA allows food producers to label their products 'zero' if they contain less than 0.02 oz (0.5g) of that particular ingredient per serving. Eat several servings of a supposedly zero-fat or zero-sugar food, and you could end up unwittingly consuming fat or sugar without meaning to.

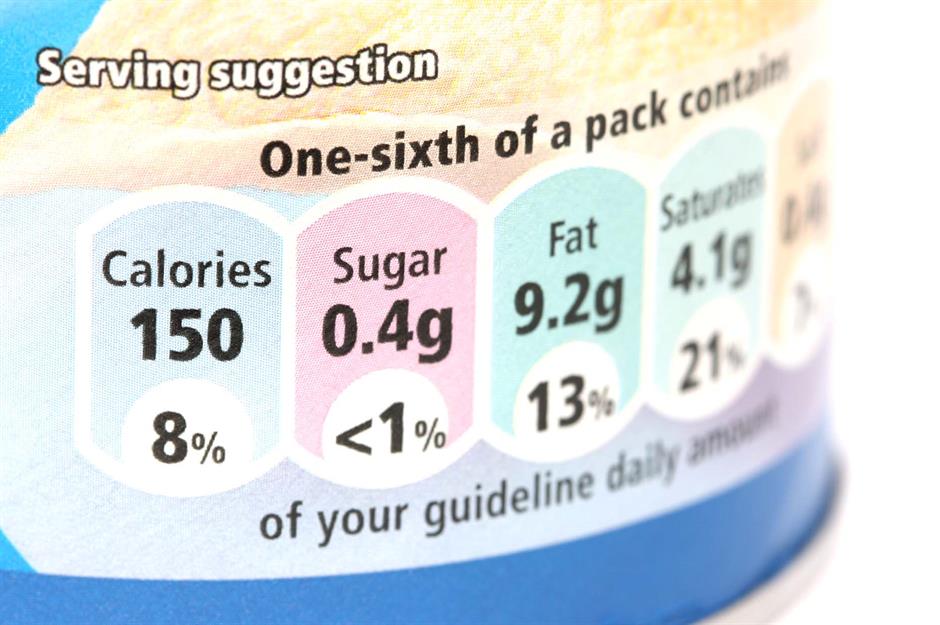

Serving sizes can be misleading

Serving sizes are often used to manipulate consumers into buying certain products, too. From a visual perspective, if the food is displayed on the packaging, it's very rarely just one serving – meaning the consumer thinks they’re getting more for their money. Not only that, but when it comes to foods like crisps and popcorn, the amount of calories, fat and sugar will normally be listed per serving rather than per pack, making them appear healthier than they are. After all, you're more likely to devour an entire packet of crisps rather than a single serving, meaning you're ingesting extra calories, fat and sugar.

Labels are often padded

Another trick that consumers need to be aware of is label padding. In simple terms, this is when food manufacturers (especially processed food producers eager to jump on a health food trend) add a minuscule amount of something 'good' (think whole grains, or a so-called superfood) in order to then be able to market the item as 'healthy' or containing a desirable mineral, vitamin or ingredient. Legally, there are no rules that prevent manufacturers from doing this.

Anything 'baked not fried’ should be approached with caution

It's safe to say that most of us would assume 'baked not fried' products are much better for us – but there are other ways in which fat can be added in order to make food taste good. Compare the labels of both fried and baked crisps, for example, and you might just find that the saturated fat content is similar (and rather high) in both.

Meat and dairy can be hidden

Vegetarians and vegans might want to check the label on presumably vegetarian foods twice. For example, many brands, fast food outlets and restaurants use lard (or pork fat) to inject an especially savoury and rich flavour into refried beans. Check before ordering, and take time to read labels when shopping – in the US, popular brands like Old El Paso and Rosarita both specify lard in the ingredients list on their traditional refried beans.

Fish products often hide in plain sight

If you have a fish allergy or are vegan or vegetarian, make reading food labels a matter of course; even seemingly innocent products can contain surprising ingredients. Worcestershire sauce, for example, hides a secret ingredient that's been used in the making of this condiment since its inception in 1835: anchovies. Other products that you might be surprised to find contain fish-based ingredients include certain brands of miso paste and some ready-made curry bases.

There's seaweed in dairy-free milks

Seaweed is a popular ingredient in many dishes across the Asian continent – but did you know that an extract made from seaweed is also used as a thickener, stabiliser and emulsifier in many common supermarket foods too? Carrageenan is commonly added to many dairy alternatives, including soy, rice and almond milks, and it also often replaces gelatine in plant-based products. Despite being a natural ingredient, there is some evidence to suggest that carrageenan can have a negative impact on the digestive system.

There might be antibiotics in your meat

It might not be mentioned on the label, but meat products can contain antibiotics. The use of antibiotics to promote growth in animals was banned in the EU in 2006, and in the US in 2017. In 2022, the EU prohibited the use of antibiotics on healthy animals altogether, and preventative use has also been restricted. However, there are still serious concerns about the close links between the overuse of antibiotics and increased antimicrobial resistance in countries that still allow antibiotic usage.

There may be added water in your chicken

Injecting poultry with a saltwater solution – a process often referred to as plumping – has been common practice for decades. Manufacturers claim it makes the meat juicier and improves the taste, but there are different controversies surrounding the issue. Some argue its main aim is to grow profits due to the increased weight of the meat. It's also worth noting that, as the solution is saltwater-based, it can increase the sodium levels of the product, meaning you might unwittingly consume more salt than you mean to.

'No artificial additives' doesn't mean no additives at all

Many food producers will use the ‘no artificial additives’ claim to trick consumers into thinking that a product is healthy. But, rather confusingly, food that's not packed full of artificial additives can still contain additives that are produced from natural substances, which are artificially added to the product.

Tartrazine is best avoided

Many processed foods such as cakes, ice cream, soft drinks and sweets contain artificial colours, with E102 or tartrazine being one of the most common. This synthetic additive, which is used to imbue products with a bright yellow colour, was linked to childhood hyperactivity in 2007, which resulted in an EU requirement to put a warning label on products containing it. There's no such requirement in the US, though, and there are still plenty of processed foods on supermarket shelves that contain tartrazine.

Carmine can cause allergic reactions

Carmine is a red food colouring that's made by boiling the shells of cochineal bugs (a type of beetle), and it's commonly used in foods like sweets, lollipops and dessert sauces. Although it's harmless to most, it can cause severe allergic reactions – so in the US, the FDA requires it to be labelled clearly on products. If you see carmine, cochineal extract or E120 on the label, you might want to steer clear of it.

That shine may be down to E904

A natural resin that's often used to add a glossy coating to products like jellybeans, shellac is approved for use in food in most countries, typically labelled as additive E904. Be warned, though: it can also be found in nail varnishes, wood finishes and furniture polish. The sticky substance, excreted by the female lac bug native to the forests of India and Thailand, can even be used on citrus and other fruits as a surface treatment, giving them a glossy, appealing shine. To avoid consuming it, seek out unwaxed fruit where possible.

Your bread may contain L-Cysteine

Chances are you currently have a shop-bought loaf of bread, packet of biscuits or cake in your kitchen. L-Cysteine, called E920 on product labels, is an amino acid that's used to strengthen the dough in, and improve the shelf life of, such products. What might surprise you is that this additive is found in duck and chicken feathers, cow horns, pig bristles and even human hair, all of which are dissolved in acid to isolate the L-Cysteine compound. Although most L-Cysteine is now synthetically produced, the majority of labels still don't disclose where the additive was derived from.

Those smoky notes may be synthetic

It might surprise you to know that the deep, smoky flavour in foods such as barbecue sauces, baked beans, hot dogs and beef jerky comes courtesy of a manufacturing process. It’s created by burning wood or sawdust, then capturing the resulting smoke condensation in cold air. The droplets containing the intense smoky aroma can then be used as an alternative to actual smoking. On labels you'll typically see it listed as smoke flavouring – it's what gives sauces like Heinz Classic Barbecue Sauce and Sweet Baby Ray's Original Barbecue Sauce their signature smoky depth of flavour.

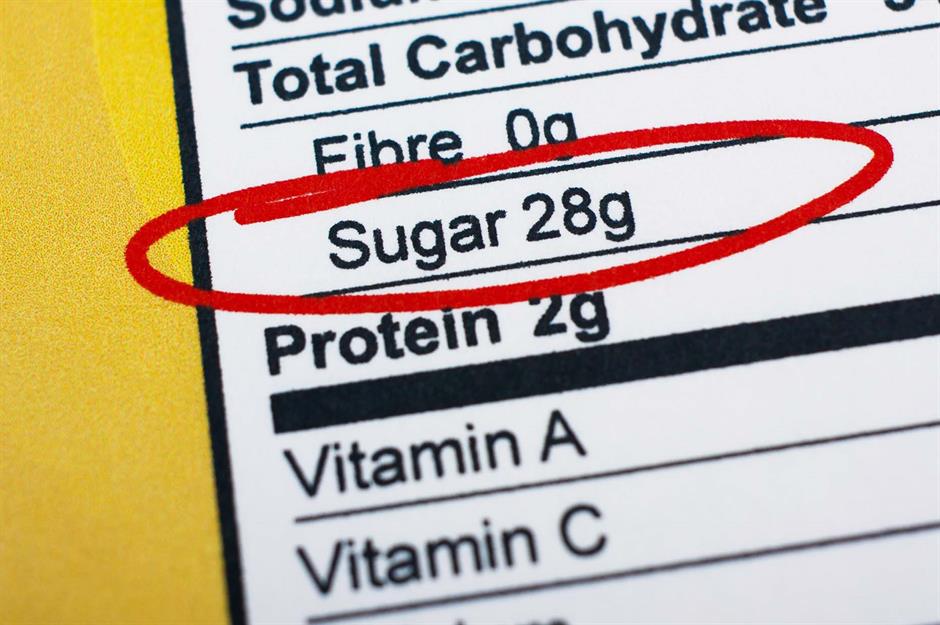

Sugar isn't always obvious

Nowadays, most people are pretty clued up on sugar and know that products with a high sugar content are best avoided. But this also means food producers have become much smarter about hiding sugars. For example, sugar can appear in ingredients lists as glucose, lactose, sucrose, dextrose, maltose, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), honey and maple syrup, amongst other names. This means that the total sugar count can be hidden in the ingredients list, or made to look smaller than it is by naming each type of sugar used. To avoid being duped, always check the total sugar content in the nutritional fact box.

'No added sugar' doesn't mean NO sugar

Another trick used by food producers is claiming that there's no added sugar in a product – which automatically makes consumers assume it's a healthy option. However, it's worth thinking about the sugar that's already contained within the product. Products like milk and fruit contain sugar naturally, so if something is made with those ingredients, it will automatically contain sugar too.

Your truffle oil probably doesn't contain truffles

Often, it's more surprising what isn't in truffle oil than what is. It's no secret that fresh truffles are pretty hard to come by, which makes them incredibly expensive. So it shouldn't really come as a shock that most truffle oils have never been anywhere near a real truffle. If you've tasted both freshly shaved truffles and foods drizzled with truffle oil, you'll know the flavour differs considerably. This is because most oils are infused with synthetically made ingredients, specifically 2,4-Dithiapentane.

White chocolate isn't really chocolate

Though milk and dark chocolate are made from cocoa solids – cocoa beans removed from pods, fermented, dried, roasted and cracked open – white chocolate isn't. Instead, a blend of cocoa butter, milk products, vanilla, sugar and fatty emulsifier lecithin is what makes up this sweet confectionery item, meaning that technically it isn't really chocolate at all.

Cans of pumpkin might be pumpkin-free

Many of us enjoy a range of baked pumpkin treats come autumn time – but if you use the canned stuff, you might not be cooking with pumpkin at all. One of the most popular brands in the US, Libby's Pure Pumpkin, actually uses Dickinson squash – a close relative of butternut squash. How can it be marketed as '100% pure pumpkin', you may wonder? Well, it's because the FDA allows it, thanks to a policy that says products made from 'golden-fleshed, sweet squash or mixtures of such squash and field pumpkin' can be sold as pumpkin.

Now discover 35 food mistakes most people make all the time

Last updated by Lottie Woodrow.

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature

Most Popular

Reviews 31 unbelievably sugary cereals from around the world