What is Champagne and other fizzy facts

Let’s get fizz-ical

Nothing says celebration like Champagne. For many of us, popping open a bottle of bubbles is the default way to mark good news or to toast to success. It’s also a byword for luxury and indulgence. More than 320 million bottles of the festive fizzy stuff were sold worldwide in 2020 (second only to Prosecco). From the stories behind the most prestigious Champagne houses to how we drink at home, here’s how the king of bubbles conquered the world.

Accidental invention

Perhaps a mistake, rather than necessity, is the true mother of invention. The story goes that, in the 15th century, too-cold temperatures disrupted the fermentation of wine and caused excess carbon dioxide bubbles. There’s also some evidence to suggest the English invented something akin to champers, or were at least pretty partial to fizzy wine. A 1662 paper on winemaking by scientist Christopher Merret describes how English merchants would add sugar and molasses to make wines frothy and sparkling.

A monk named Dom

You may have heard of Dom Pérignon – the Benedictine monk, that is, rather than the Champagne named in his honour. Fizz in some format almost certainly existed before he was around but Pérignon is widely credited with helping to develop the Champagne region’s wines from still reds to biscuity sparklers. Perhaps most crucially, he helped to create a method of successfully producing white wine using red grapes, extracting the juice without much contact with the skins (which impart the colour).

Capturing the sparkle

In the Middle Ages, fizz in wines from the Champagne region of France was an unwanted side-effect of incomplete fermentation creating tiny carbon dioxide bubbles – not especially desirable in the red wines then prevalent in the area. Pérignon was one of the winemakers who looked at how to control this process and create sturdier bottles sealed with corks, capable of ‘prise de mousse’ or ‘capturing the sparkle’. These new and improved sparklers became a firm favourite among the wealthy and in royal courts.

Rooted in place

The name comes, of course, from Champagne, whose reputation for world-class wines dates back to them being chosen for the 5th-century baptism of Clovis I, which marked the birth of the kingdom of France. Located east of Paris, vineyards stripe the region’s plains and hillsides. The area has the ideal conditions for grape-growing, including chalky limestone soils, regular rainfall, a temperate climate and moderate sunshine, helping achieve a balance of sugar and acidity.

Below ground

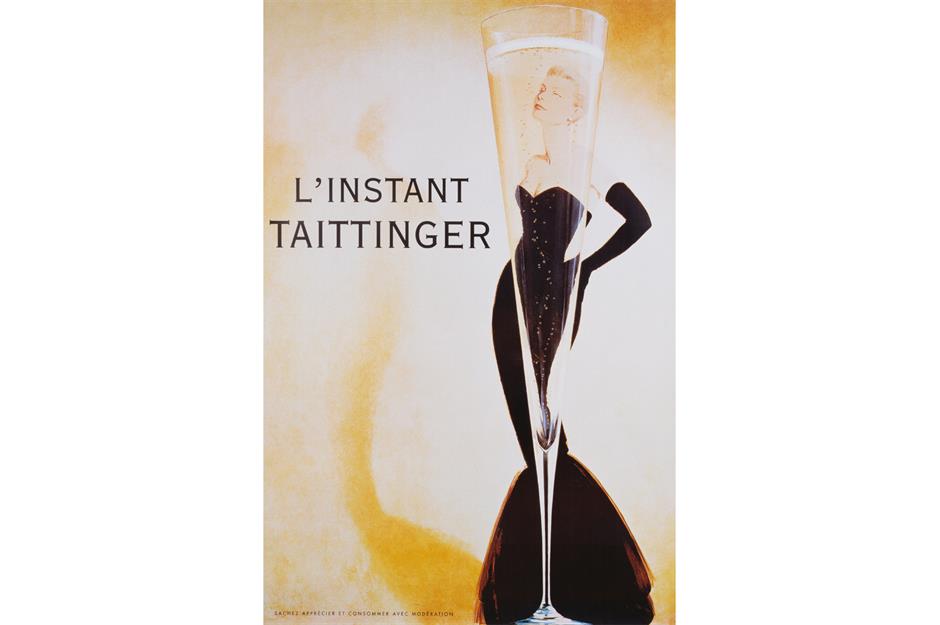

So iconic is the wine and its region that Champagne’s hillsides, houses and cellars were awarded UNESCO World Heritage status in 2015. The cellars and caves where the Champagne is produced and aged are especially fascinating. Taittinger's caves, for example, are built into the crypts and vaults of the now-destroyed Saint-Nicaise Abbey, which dates back to the 13th century.

The power houses

Around 72% of Champagne – and 87% of fizz exported from the region – is made by the bigger producers or ‘houses’ such as Taittinger, Moët and Veuve Clicquot. Yet the 360 houses only own around 10% of the vineyards that stripe the region, which has led to a system where they can purchase grapes from smaller growers after each year’s harvest. Recent years have seen a rise in Champagnes made by smaller, independent producers and local co-ops.

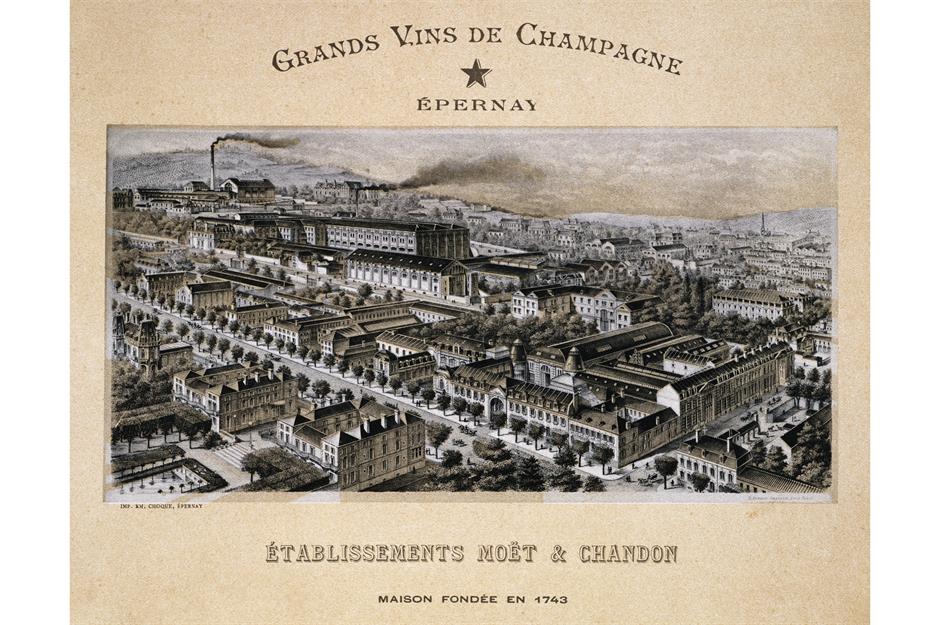

Best in bottle

Dom Pérignon remains a byword for fine fizz, though our 17th-century monk might be disappointed to know it’s only the fourth best-selling in the world. Top of the cork pops is Moët & Chandon, which outsells its competition year after year, followed by Perrier-Jouët and Veuve Clicquot. The real winner is Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (known as LVMH), which owns five of the top 10 sellers.

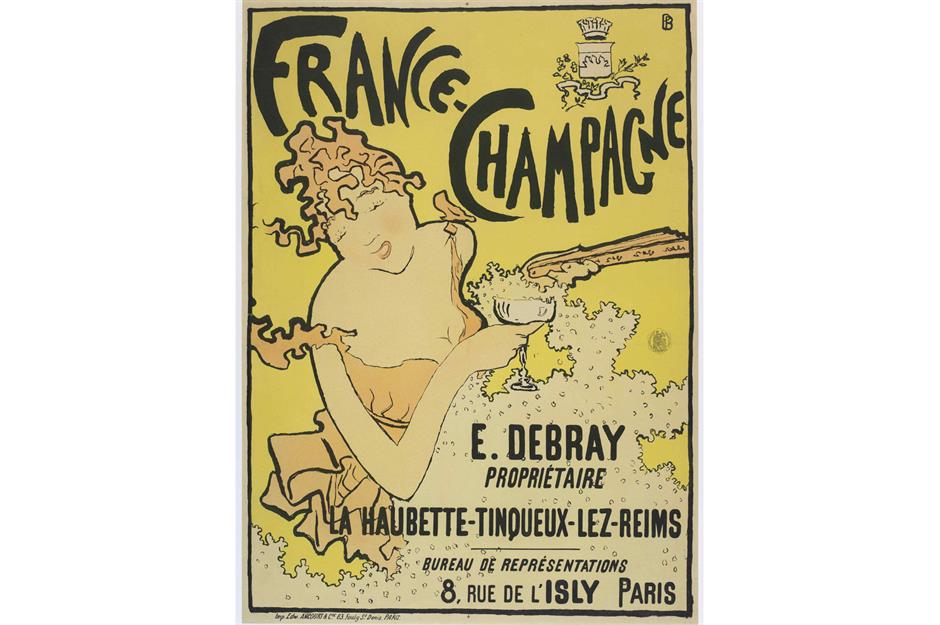

The yellow widow

A bottle of Veuve Clicquot is instantly recognisable thanks to its striking yellow label, yet the meaning behind its name is a little more sombre. ‘Veuve’ means ‘widow’ in French and refers to Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin Clicquot. She was widowed aged 27, seven years after marrying the company’s heir François, and became the first woman to run a Champagne house. It was Madame Clicquot – who made the company a success, creating the first ever single-vintage Champagne (in 1810) and selling directly to customers to boost profits.

On the grapevine

There are strict rules about how Champagne is made, including what grapes can be used. The vast majority of bubbly produced in Champagne is made with pinot noir, meunier and chardonnay, which bring structure, fruitiness and light floral notes. But there’s actually a total of seven officially permitted grapes, with pinot gris, pinot blanc, arbanne and petit meslier the other, far less common varieties. It’s the blend that gives each Champagne a unique flavour. Veuve Clicquot favours pinot noir, for example, whereas Dom Pérignon is made primarily from chardonnay.

Champagne method

To be legally labelled Champagne, bubbles must be produced in the region following ‘Méthode Champenoise’ or the Champagne method. It starts with various still wines, individually fermented to form the base and used by the winemaker to create a blend or ‘cuvée’. It’s this step that gives each Champagne house its signature style and maintains consistency year-on-year.

Discover how more of your favourite foods and drinks got their names

Brilliant bubbles

The blended wine is mixed with a little yeast, sugar and sometimes grape must (juice with skins, stems and seeds), known as the ‘liqueur de tirage’. The wine is bottled and sealed so the carbon dioxide created is trapped inside during this secondary fermentation and has to dissolve into the liquid – creating those deliciously delicate bubbles. And lots of them too: French physicist and 'effervescence' specialist Gérard Liger-Belair worked out that an average bottle of Champagne contains around 10 million bubbles.

Ageing gracefully

The yeast eventually dies and becomes a deposit known as the lees, the unlikely source of Champagne's complex flavours. Champagne is legally required to age ‘on its lees’ for at least a year and to spend a total of at least 15 months in the bottle. Vintage wines require at least three years in the bottle before being released for sale. Many are kept in the cellars for much longer and up to 10 years for vintage bubbles.

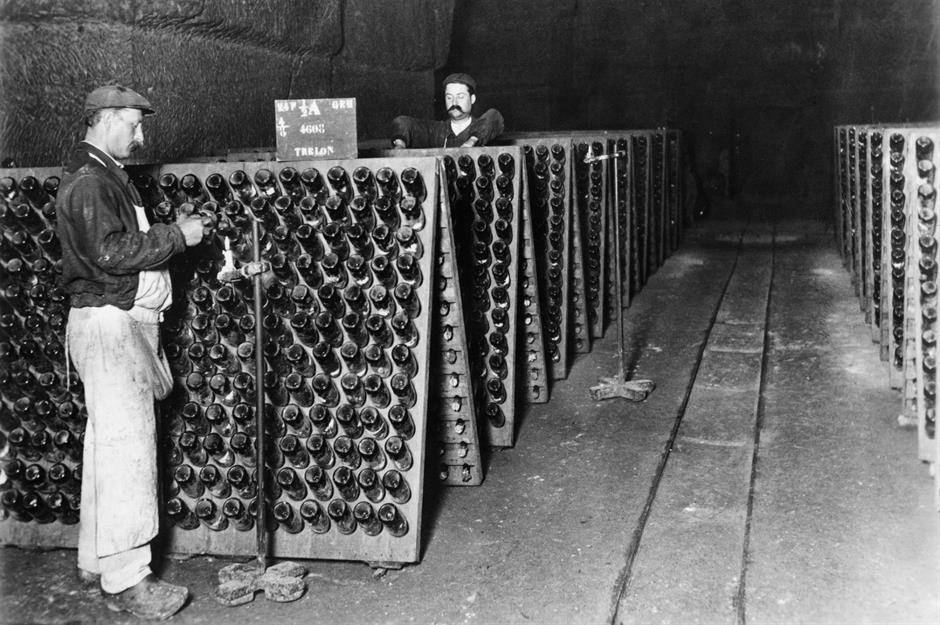

Riddle me this

Another important part of the process is the ‘riddling’ of the bottles, which aids in the removal of the dead yeast particles. This regular rotation – traditionally done by hand but now more commonly done by machine – helps the lees to gradually descend to the neck of the bottle towards the end of the ageing process. Once it forms a plug, the bottle necks are plunged into freezing liquid so the yeasty blocks pop out or ‘disgorge’ upon opening – with minimal loss of the precious champers.

Final dose

The final step before the wine is corked and sealed up smartly with a wire cap and collar is the bit that determines the sweetness. The disgorged Champagne is usually topped up with a solution of sugar, still wine and grape must known as liqueur d’expédition. Brut Champagne has anything from zero to 12g (0.5oz) of sugar added per litre (33.8 floz), demi-sec can have up to 50g (1.8oz) while the sweetest, doux, requires 50g (1.8oz) as a minimum. Extra brut and brut nature styles, which are becoming increasingly popular, often have no dosage at all.

Taste of England

It was the English palate that led to the drier styles of Champagne first being produced. When Madame Clicquot, having taken over her late husband’s Champagne house, began to export her fizz to England, she found they preferred it to be less sweet. Responding to this ‘goût anglais’ or ‘English taste’, she created a dry version with the now-iconic yellow Veuve Clicquot label (her sweeter Champagne was wrapped in a white label).

From Russia with (sweet) love

In contrast, the Russian palate found the French fizz wasn’t sweet enough. A tooth-tinglingly syrupy Champagne was created to satisfy these sweet teeth, classified as ‘goût russe’ or ‘Russian taste’. It was roughly six times sweeter than our sweetest Champagne today, containing up to 330g (11.6oz) of sugar per litre (33.8 floz). Russia played a significant role in Champagne’s popularity, becoming one of the world's largest consumers of the fizz in 19th century – as this 1897 Vanity Fair portrait of Tsar Nicholas II suggests.

Fizzy friends

Champagne isn’t the only fizz made using the Champagne or traditional method. Highly-regarded crémant wines, made in eight regions in France plus one in Luxembourg, follow the same stringent process, as do Spanish cava and South African ‘Methode Cap Classique’ sparklers. Many wineries in the US, especially California, and a growing number of English sparkling wine producers also use the traditional method and, often, the same grape varieties.

Different strokes

The Champagne method isn’t the only way to make sparkling wine. Prosecco, which has overtaken champers as the world’s biggest selling fizz, is made using the more modern tank method, where the second fermentation takes place in a tank rather than individual bottles. Asti is made in the same way but skips the second fermentation, which is why it’s sweeter and lighter in alcohol. Another way is the increasingly popular ancestral method or ‘pet-nat’, where the initial fermentation is paused midway for several months before resuming once bottled.

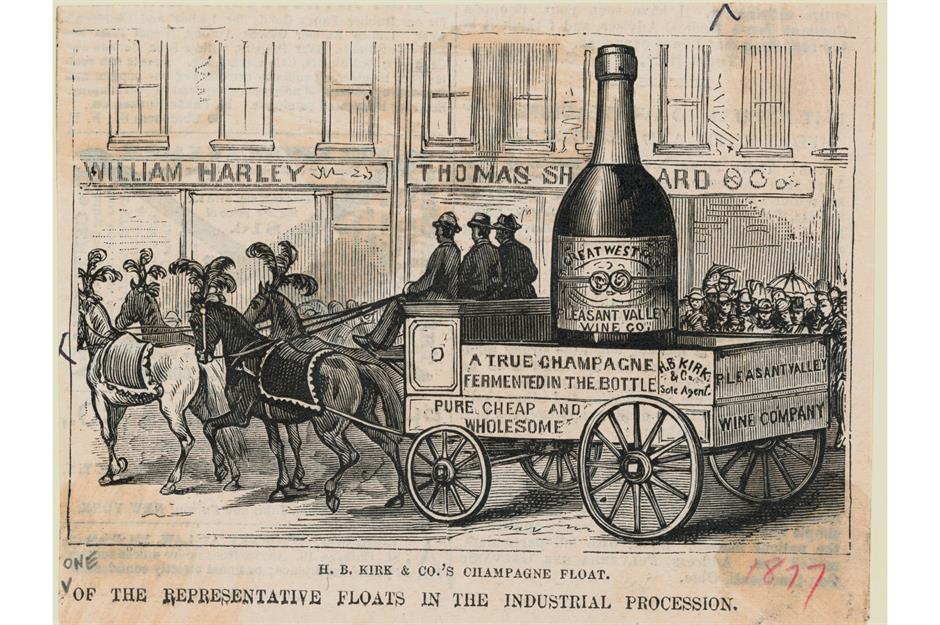

Exceptions to the rule

The term Champagne was protected as part of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after the Second World War, so it could only refer to fizz made using the traditional method from grapes grown and fermented in the Champagne region of France. But, as the US didn’t ratify the treaty and was just entering Prohibition, it wasn’t applied to wine producers there and they were free to label their sparkling wines as ‘champagne’. A 2006 agreement changed that but houses which had previously used the term were allowed to continue.

A classy glass

It isn’t enough to just select the best Champagne. The glass you drink it from matters too – and it has to be a tulip-shaped (rather than straight-edged) flute, according to trade association the Comité Champagne. The shape helps to trap the aromas while the height allows the bubbles to develop without going flat. Speaking of which, don’t even think about pouring fizz into a smeared, less than sparkling glass. There’s nothing surer to burst your bubbles than detergent or soap residue.

A real coupe

Coupes – the shallow, saucer-shaped glasses – were once the champers vessel of choice. But the Comité Champagne has some strong opinions about their suitability (in short: they’re not right for bubbles). A popular legend is that the coupe was modelled on one of Marie Antoinette’s bosoms but that has been widely debunked. Still, the glasses have a certain glamorous, vintage appeal even if they aren’t the best for keeping your bubbles bubbly.

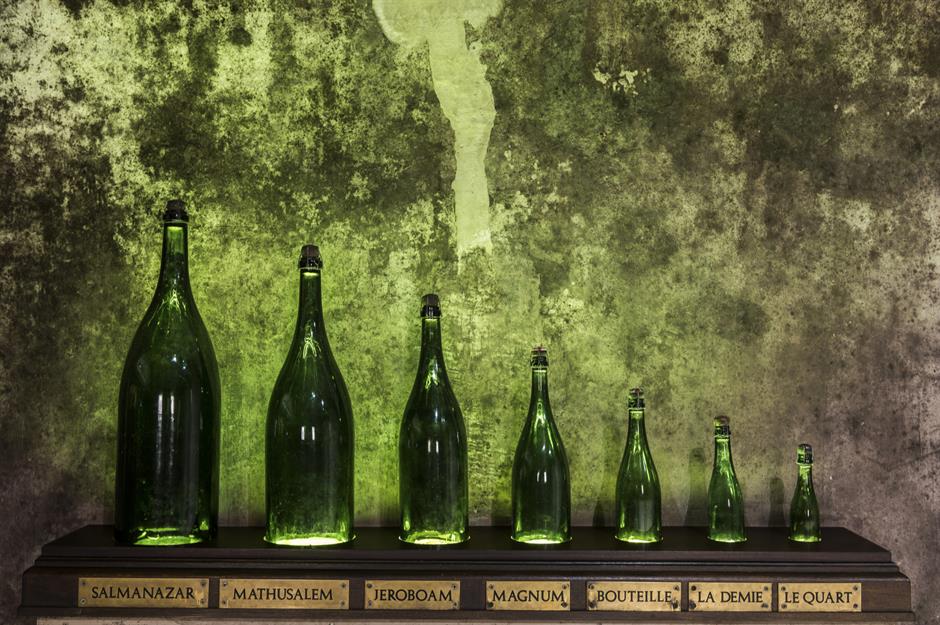

Bottle it

What’s better than a bottle of bubbly? How about a bottle that holds 30 litres (8 gallons) of the fabulous fizzy stuff? The rare midas or melchizedek holds the equivalent of 40 standard 750ml (25 floz) bottles of champers and is the biggest of all the bubbly holders, followed by a primat (36 bottles) and the souverain (35 bottles). More common (though still pretty indulgent) are the Jeroboam, holding four bottles, and the 1.5-litre (51 floz) magnum.

Save or slurp?

The celebratory nature of Champagne means that, while we might be tempted to pop the cork straight away, we often like the idea of laying the bottle down to bring out for a special occasion. But actually, most Champagne is released at its optimum for drinking and should be enjoyed within three years of purchase to be at its bubbly best. While they are stored, bottles should be kept at low, ambient temperatures of around 10°C (50°F) away from direct sunlight.

Very vintage

Even the finest Champagnes don’t tend to be laid in the cellar for as long as the one that was found in a wooden hull at the bottom of the Baltic Sea in 2010. Nestled among 167 other bottles of bubbly, all in near-perfect condition thanks to the constant temperatures and lack of sunlight, the Veuve Clicquot was estimated to be around 170 years-old and produced under the reign of Madame Clicquot herself. It set a new record at auction in Finland, selling for €30,000 (£27,193 or $37,713).

Famous fizz fans

It’s inevitable that such an illustrious libation would garner plenty of starry attention. A favourite story is that Marilyn Monroe bathed in the most luxurious of bubbles at least once, with 350 bottles emptied into her tub with gleeful abandon. James Bond is another (fictional) fan. More famous as a martini drinker, he is often spotted on screen sipping champers and Bollinger officially became his fizz of choice in 1979. Hopefully the bottle wasn’t shaken or stirred.

Discover these fictional foods and drinks that actually exist

Comments

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature